While in my senior year of college, I discovered Ovid’s Erotic Poems. Reading a few of them to my friends convinced them that they were too funny to keep to ourselves. And so, my entire floor of the dormitory was invited to hear the poems. This series of readings won the affectionate nickname “Wisdom of the Ancients” and continued until I ran out of Ovid and turned to Catullus. Unfortunately, these poems proved too disturbing for the members of my hall, and the series ended promptly.

I promise not to post any profane Catullus here–especially since he can write beautifully when he wants. Instead, I’ll start with some of the best of Martial’s epigrams. One of which, I have already posted about. Essentially, I shall use the same format as was used in that article: writing the poem in the original, translating the poem, and elucidating on the ideas contained therein. I hope to be able to do this daily. Today, this series starts with the fourth epigram of Martial’s tenth book of epigrams. Enjoy!

Qui legis Oedipoden caligantemque Thyesten,

Colchidas et Scyllas, quid nisi monstra legis?

Quid tibi raptus Hylas, quid Parthenopaeus et Attis,

Quid tibi dormitor proderit Endymion?

5Exutusve puer pinnis labentibus? aut qui

Odit amatrices Hermaphroditus aquas?

Quid te vana iuvant miserae ludibria chartae?

Hoc lege, quod possit dicere vita ‘Meum est.’

Non hic Centauros, non Gorgonas Harpyiasque

10Invenies: hominem pagina nostra sapit.

Sed non vis, Mamurra, tuos cognoscere mores

Nec te scire: legas Aetia Callimachi.

You who read about Oedipus and endarkening Thyestes,

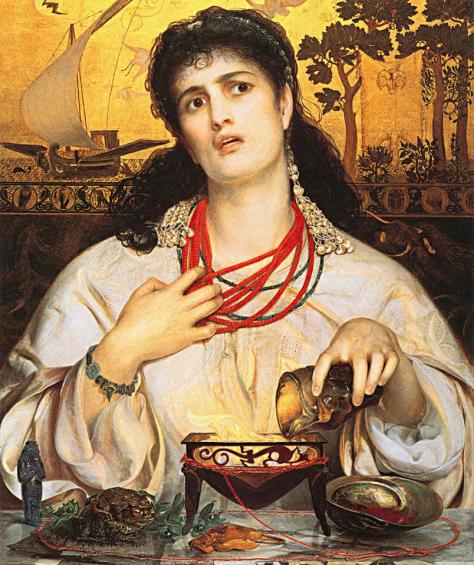

Medeas and Scyllas, what are you reading about except monsters?

What help to you is stolen Hylas? What good to you is Parthenopaeus and Attis?

What benefit is the sleeper Endymion to you?

Or the boy slipped of his falling wings? Or Hermaphroditus

Who hates the watery mistress?

Do these empty laughing-stocks of a miserable page help you?

Read this work of mine, because Life can say “The work belongs to me.”

Here, you will find no Centaurs, Gorgons, and Harpies:

Our pages understand man.

But you wish, Mamurra, neither to recognize your ways

nor to know yourself: may you read Callimachus’s Aetia.

Analysis of the Epigram’s Themes

The proper names are organized in a beautiful way so that the word monstra strikes the reader more strongly. After all, Oedipus and Thyestes are people–as is Colchidas, literally “women of Colchis” refering to its most famous personage, Medea. Scylla is the only being having the form of a monster, but Oedipus for sleeping with his mother, Thyestes for eating his son, and Medea for slaying her sons are all monsters through their deeds. The fact that Oedipus and Thyestes are singular while Medea and Scylla are written in the plural form reflect on the repetitiveness of epic. Even though Oedipus’ and Thyestes’ crimes are singular, many epics are written about them–the same as we see with Medea and Scylla.

Another thing to reflect on in the first two lines lies in that Oedipus and Thyestes unwittingly did wrong. Also, Scylla is a monster and so has neither rational or moral agency. Why is Medea there then when she wittingly slew her two children in order to revenge herself on Jason? It cannot but be because the ancient pagans viewed women as irrational. Just a little example of ancient mysogyny and perhaps even the trepidation with which men held women in the ancient world. Naturally, men are stronger than women, but one always views beings which one considers irrational with a bit of fear. Hence, women were kept locked up by their fathers and husbands in the ancient world lest they follow their passions and disgrace the family through adultery or fornication. Thus, the first two lines strike us with the irrationality and unreality of epic.

The next four lines contain examples of pretty boys. When we think of epic, we usually think of heroes like Hercules, Achilles, Odysseus, etc. But, Martial would have us focus instead on the many pretty boys who have little agency in the stories featuring them and are pushed around by fate. Even the most masculine of them, Parthenopaeus of the Seven against Thebes, becomes diminished by his association with boys who became love slaves of various goddesses and nymphs. His masculinity is especially painted with dark colors by being placed next to Attis, who castrated himself in order to become the devotee of the goddess Cybele. Lastly, Hermaphroditus hates the watery mistress because a certain nymph attempted to rape him while he swam in her waters–the ultimate form of emasculation. Even the position of Hermaphroditus between amatrices and aquas give the impression of him being overwhelmed. But, he must submit to fate no matter how much he hates it. All this asks how epic can produce good men when we see so many examples of boys on one hand and monsters on the other.

The Latin word ludibria in line seven can mean mockery, derision, object of derision, laughingstock, or plaything. It seems to refer to all the “heroes” of the epics above as well as to the epics themselves, which are vana–“empty or vain.” I also believe that the position of vana colors iuvant to indicate that epics are vain helps to understanding life. Also, one might be tempted to look at miserae chartae (“of a miserable page”) as miserarum chartarum (“of miserable pages”). But, the latter, by being plural, seems to condemn only certain works of epic and myth, while the singular condemns the whole class of mythology and epic to perdition, making miserae chartae much stronger. All epic is cut from the same silly cloth!

In the next line, Martial personifies life–vita–as if to show Life itself giving an endorsement of his poetry. It is also worth noting that this line and the next three provide and interlocking order of themes: real life, myth, real life, myth. The last line contains the philosophical dictum te scire–“to know thyself”–in opposition to Callimachus’s Aetia, which may correctly be called a work of belles lettres. The epigram asks the reader to choose between real knowledge and fantasy. (St. Augustine, if he read this poem, must have loved it.)

To end this article, I must say that I love the juxtaposition of Mamurra and Callimachus in the final lines. Mamurra was one of Julius Caesar’s henchmen, while Callimachus was a famous Alexandrian poet. Martial offers the chance to Mamurra to learn to repent of his evil life through reading works which show how to live a good life–poetry based on reality and philosophy. On the other hand, Callimachus seems to be even more criminal than Mamurra by having written such nonsense as Aetia. The poem even suggests that myth produces such criminals as Mamurra.