In my friend’s article on Tolkien, he adduced a rather curious point against Lord of the Rings: hardly any of the protagonists died. At first blush, this struck me as a fine absurdity! Annoyed by a dearth of death! Fie! One ought to be more prone to criticize a work because too many of the characters die, as we see in George R. R. Martin’s Song of Ice and Fire. Or are we to consider killing off beloved characters a virtue? (Perhaps, if the story goes on for far too long, as in Sherlock Holmes, but we know how Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s attempt to kill off Sherlock Holmes ended!) Yet, below J D Thomp’s article, a commentator expressed aggreeance with his criticism! This forces me to give the idea serious consideration.

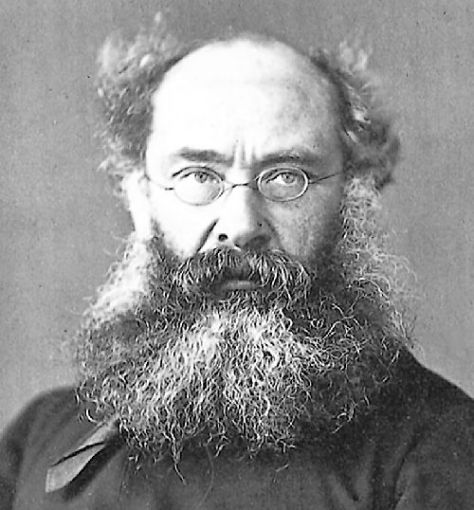

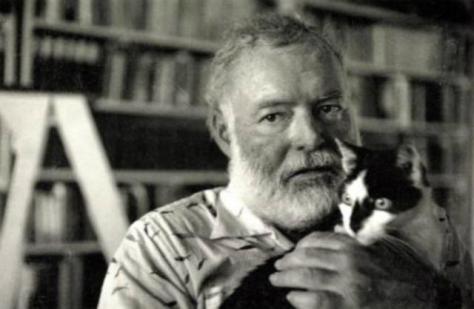

There used to be an excellent WWII show called Combat!, where the writers would throw darts at a board with the characters’ pictures to see which character should die in a particular episode. The fact that one’s favorite character could die at any moment created a great sense of realism in that show; however, a similar callousness seems inappropriate in an epic fantasy or, rather, this epic fantasy. A writer must pick what truths he wishes to examine in a book, and the mortality rate on a medieval battlefield or on a desperate journey does not concern Tolkien. But, I will say that casualties among well armored persons, as our heroes were during the major battles of the work, were indeed very low in the Middle Ages. Otherwise, I expect that Medieval noblemen would have had the same attitude to war as Hemingway and the other Lost Generation writers.

You can bet they’re all having the time of their lives!

In a prior post, I mentioned how themes of mercy, providence, and sin abound in Lord of the Rings. It does not make Providence look very provident if Gimli (when cut off at Helm’s Deep), Pippin (in fighting the Black Rider), Gandalf (in Moria), Sam (Mordor), and Frodo (Mordor) all end up dead by the end of the book, does it? (Of course, if one wishes to examine the problem of evil, so many deaths is quite appropriate.) There were ample opportunities for all of these characters to die! As for the Deus Ex Machina rescue of Sam and Frodo, that fits in with the above three themes. “Blessed are the merciful, for they shall be shown mercy.” As Frodo spared Gollum’s life despite Sam’s urging to kill him, it is no wonder that Frodo should be providently rescued. If the ring represents sin, salvation is naturally found when sin is destroyed–and the advent of salvation is as marvelous as it is unexpected!

I should adduce one more thing for consideration. I have written the first draft of a novel, where one of my favorite characters dies–and relatively early in the work. Note my wording: “where one of my favorite characters dies.” Does this not sound altogether passive? That’s because it is so. In the story in my mind, I simply saw Thord dying in that battle. To write otherwise would be false to the story. It would not surprise me if Tolkien faithfully passed on a story he felt that he was given.

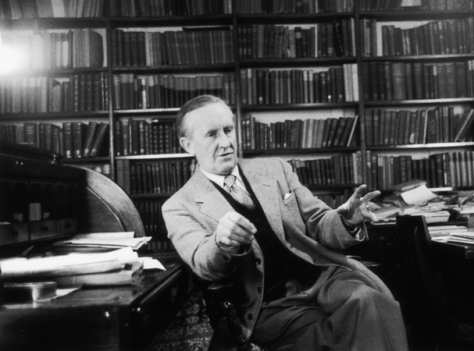

I want a library like that.

And should this make us upset? No! When a great character should die, let him die and take a piece of our hearts with him. If a great character lives, let us rejoice that he obtains the glory and peace due to him.