Monthly Archives: June 2014

Impression of the Dresden Files

While I was a member of the Science Fiction Book Club, I purchased an omnibus edition titled Wizard for Hire by Jim Butcher. It includes the first three novels of the Dresden Files: Storm Front, Fool Moon, and Grave Peril. I devoured these three novels in short time. I’d say that it took reading all three novels in order to come to a general opinion of the series, which is now at sixteen books. These books are exciting page turners, but they smack of being formulaic. It’s a very good formula where the obstacles keep mounting for the hero, but I find myself leery of formulaic plots. After all, can’t one keep changing the details and villains and continue to churn out thrillers? One of the things I like about the classics is that the science of writing a story was not well known. The plots might be slow or full of errors when looked upon from the science of novel writing, but they’re more interesting for all that.

For all the sense that Butcher follows a kind of formula, the details and characters in each story are brilliant and lovable. These areas of the novels and the prose itself contain his artistry and great sense of humor. I might describe his hero as a Philip Marlowe with the physical features of Sherlock Holmes–sans the master detective’s athleticism. But, Butcher adds the twists of Harry Blackstone Copperfield Dresden (what a name!) being a wizard and perfect gentleman. Butcher also goes to great lengths to making Dresden seem more human and less hard-boiled than Marlowe. Another recurring character is Karrin Murphy. I find her too touchy and too much of a feminist. It’s cool that she’s a Aikidoka (Though, her trophies prove that she’s numbers among the sport Aikidoka, whose art is less traditional), a sharpshooter, and a tough cop; but, she’s way too demanding. (I was happy to see less of her in Grave Peril.)

Besides Raymond Chandler’s detective novels, I’d say that he owes much to H. P. Lovecraft and Christian writers like Tolkien and C. S. Lewis. Concerning the former, the vast array of supernatural villains and the idea that giving in to evil never pays are very Lovecraftian. The ideas of sexual purity, the positive presentation of faith, and the constant battles between good and evil evince a Christian moral background. Though Harry Dresden himself seems to be kind of pagan–he still believes in God, but is not sure whether God is caring, Butcher introduces a very Catholic character in the paladin Michael, the Fist of God. Virtuous characters are often accused of being boring, but Michael, with his stoic insistence on morality, quiet faith, and a bastard sword named Amoracchius, stand as one of the series greatest characters. Michael appears in Grave Peril, and the opportunity to read more of him and Dresden battling villains will likely convince me to pick up more novels.

So, I have a rather positive impression of the Dresden Files. Though the plot for his modern fantasy thrillers reveal a formula, the writing, characters, and other details he adds are very interesting. They feature suspenseful and action-packed battles between good and evil. So, these novels are great fun and I recommend that you read a few of them. Fool Moon, which dealt with werewolves running rampant in Chicago, stood as my favorite of the three.

Review of Vikings: A History of the Norse People

Michael J. Dougherty provides the reader with an excellent overview of Viking history and culture. Vikings: A History of the Norse People‘s accurate portrait of Viking culture and the important events of Norse history marks it as perfect for the beginner. Dougherty, who gives every mark of expertise in the Viking age, wrote this book to challenge the caricature of Vikings as bloodthirsty savages. For this purpose, half the work covers history, while the other half investigates the culture. While the historical section felt very basic–but with interesting details which made the history come alive, the cultural section held many new facts for even a saga enthusiast like myself. His sections on Norse warfare, the Icelandic legal system, ships, and exploration are among the best in the work.

Dougherty’s work succeeds to some extent in erasing the vision people might have of the Vikings as utter barbarians. He refuses to gloss over the more savage parts of their culture however: vagabonds had no protection under the law (they might even be castrated at will); Vikings preyed upon the weak–especially monks and poorly defended towns; their religion promoted bloody conflict through requiring death in battle for entrance into Valhalla; and human sacrifice was not unknown. Those of you who watched Vikings on the History Channel will remember that night where the Vikings are high on drugs and the debauchery ends with a human sacrifice. That’s basically reproduced from a historical account of a human sacrifice which was made at a Viking’s funeral. It is little wonder that Christianity vastly improved Scandinavia!

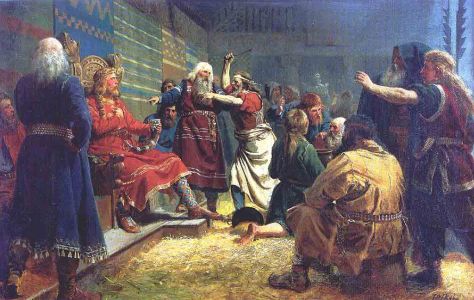

The first Christian king of Norway, Haakon the Good. His efforts at peaceably converting the Vikings to Christianity failed. It required the ruthless tactics of St. Olaf to spread the Faith. How else does one preach to Vikings?

Yet, Dougherty does a thorough job extolling the virtues of Viking culture. The Vikings excelled at brave deeds, desiring glory on the battlefield above all else. Their seafaring skills and expeditions exceeded the abilities and even imagination of their contemporaries. Their desire to be remembered in story produced great literature and poetry. And their legal system worked as a precisely oiled machine, which even gave women rights they did not have in many other parts of Europe.

All these things are described in interesting detail in this work. I especially recommend it to the beginner, but people well-versed in Viking history and culture will find interesting tidbits here as well.

Wisdom of the Ancients: Aeneas Sees Dido for the First Time

While reading through The Aeneid this time around, I found myself struck by the way Virgil weaves foreshadowing into the passage where Aeneas sees Dido for the first time. Aided by a mist thrown about him by his mother Venus, Aeneas has just been able to do a full inspection of Carthage. The Carthaginians were busy building up the city, and Aeneas has just gazed upon some artwork describing the Trojan War when Dido appears on the scene.

Haec dum Dardanio Aeneae miranda videntur,

dum stupet, obtutuque haeret defixus in uno,

regina ad templum, forma pulcherrima Dido,

incessit magna iuvenum stipante caterva.

Qualis in Eurotae ripis aut per iuga Cynthi

exercet Diana choros, quam mille secutae

hinc atque hinc glomerantur oreades; illa pharetram

fert umero, gradiensque deas supereminet omnis:

(Latonae tacitum pertemptant gaudia pectus):

talis erat Dido, talem se laeta ferebat

per medios, instans operi regnisque futuris. (Book I, 494-504)

While these marvels are viewed by the Dardanian Aeneas,

While he is astounded and fixed upon one vision, he is stuck to the spot.

The queen, Dido of beautiful curves, to the temple

strides with a great crowd of young men thronging her.

As if Diana training her chorus on the banks of the Eurota

or through the passes of Cynthus, one whom a thousand attendant

mountain nymphs gather about on this side and that; she bears

a quiver on her shoulder–stepping forward, she stands above all the goddesses.

(Rejoicings master the silent breast of Latona):

Such a woman was Dido, the happy woman bore herself so

through the middle of them, devoting herself to the work and the future kingdom.

Well, I know that I generally dislike translations of the Aeneid, and I doubt that mine is much better than what professional translators have accomplished. But, it does the job.

While reading this passage a few interesting thoughts came to my mind. Aeneas has been examining a procession of wonders after his advent in Carthage, which stupefy him (stupet); yet, he now sees one wonder to top them all: the goddess-like Dido. Though Dido is compared to a goddess, she is oddly compared to the goddess Diana. This seems disconcerting: Diana is a virgin, and none of the men she associates with meet a happy fate. Aeneas’ stupefaction on seeing her recalls how Actaeon caught sight of the goddess Diana naked, whose beauty, no doubt, stunned him. For this mistake, Diana turns Actaeon into a stag and has him torn apart by hounds. However, The Aeneid relates a story where the Diana meets an unlucky end instead.

Also, being compared to a god or goddess can often be a bad thing, because the Greek gods were so easily moved to jealousy. Misfortune often happens to people who excel in talent or beauty. A little more foreshadowing that Aeneas and Dido will not have a happy romance.

Interestingly, the crowd of young men thronging her indicate that Dido has a ton of admirers, so there is no need for her to take an interest in the foreigner Aeneas. As a matter of fact, the last two lines along with her comparison to Diana indicate that Dido would have been happiest dedicating herself to the building of her kingdom. Of course, her efforts at building Carthage into a brilliant city or even an empire (the plural form regnis futuris suggests an especially great kingdom) cause Aeneas to identify with her. This no doubt featured as part of their attraction, though Virgil shows Cupid as inspiring Dido with love later on in the story.

But, line 492 reveals the great genius of Virgil: Latonae tacitum pertemptant gaudia pectus. A five word line with the verb in the center and surrounded by a chiasmus or interlocking word order is known as a golden line. And Virgil could have made line 492 a golden line had he wished; yet, he declines to do so. The reason for this lies in that he meant this line to foreshadow the way Dido met her end. It suggests “Didonis tacitum pertemptat gladius pectus“–“The sword of Dido masters her silent breast.” (Of course, gladius does not fit the fifth foot of dactylic hexameter, but gaudia and gladius strike one as very similar in appearance.) His refusal to make this line golden points to the tragic nature of Dido’s death, which is pretty cool. Not something an English reader is going to see!

Thoughts on The Light That Failed

After hearing this blog’s co-author mention that Kipling’s The Light That Failed kept Kipling off his list of top ten novelists, I decided to read the novel myself. (Thompdjames still writes on the blogosphere, but he has been very busy writing his thesis. Check out his latest post here.) Rather than an inferior work, the novel proved to be engrossing; though, I will confess that whether or not this novel interests one might depend on one’s present circumstances, ability to tolerate stories featuring great mental suffering, and identification with the protagonist. Dick, the protagonist, is a very headstrong and prideful young man, which qualities count as his tragic flaws. Another flaw one might find with the work is that the plot mostly covers the interior thoughts of the characters and their conversation rather than their actions. Most of the work takes place in a single apartment.

Of the characters, Dick and his close friend Torpenhow stand as the most interesting. The latter acts as a restraint upon Dick’s excesses and tries to lead him to undertaking a more productive lifestyle, especially after he sees a drop in Dick’s output of paintings. Interestingly, Dick’s stubbornness often makes Dick a better influence on Torpenhow–due to the latter’s greater docility–than Torpenhow is able to be for Dick!

The novel opens with Dick conversing with his childhood friend, Maisie. Both live in the same orphanage. Yet, the opening chapter takes us from adolescence to Dick’s time as a correspondent in a military campaign. The campaign ends, and Dick and Torpenhow return to London with Dick having the intention of painting military scenes. His entrance into London shows the reader that Dick concerns himself with the appearances of things too much. For about one month, he lives by himself on bangers and mash for three square meals a day because he refuses to take out more money from the bank. You see, he wants to show London and the bank that he’s well off. I doubt anyone noticed besides himself! When he finally moves into Torpenhow’s apartments, his friend chides him for not coming to see him sooner.

There exists a movie about the book. I wonder whether it can portray Dick’s interior state as well as the book.

His preference for accidents over essence extends even to his work, as he paints the kind of pictures the public wants to buy rather than those which he might be more inclined to paint. As he becomes more famous in London, he mocks the public’s love of his work and in doing so denigrates his own paintings. But, his technical skill leads to his childhood love, Maisie, seeking his help.

His desire for Maisie stands as one of his biggest mistakes. Maisie is yet trying to improve her art, and she sees Dick as a great instructor. Basically, she treats Dick as Dick treats the public at large. She is not embarrassed about using Dick’s affections for her in order to keep receiving his instruction even when confronted by her friend, known simply as “the red haired girl,” who has real affections for Dick. Curiously, these affections somehow make Dick dislike her even more. As if her warm heart casts aspersions on Maisie’s cold, distant heart!

Overall, the story about Dick becoming more true to himself and rejecting the glamor of the world make for a good story. Unfortunately, Dick must lose a more important light before he becomes disenchanted with the glitter of the world. I leave it to my dear readers to decide whether he ends the novel happy. The Light That Failed stands as a very worthy first novel, and a good book overall.

Reminder of a Forgotten Love

I love library sponsored book sales. The books are always sold at the lowest prices because the libraries are eager to rid themselves of unwanted donations, and remarkably good books often find themselves among the undesirables. A few weeks ago, I found two Modern Library of America editions of Herman Melville’s novels–two collections which included six novels, Billy Bud Sailor, and some assorted writings. I snatched the two of them for one dollar.

This day saw a library sale at the nearby public library, which offered an opportunity for enriching myself with perhaps as stellar works cheaply. However, browsing among the fiction, historical, and political books failed to excite my interest. They all looked lifeless sitting there. I covered everything save one final section, having made the mental note that there were two books I might want–both political in scope–or I might quit the book sale entirely. This last section happened to be the fantasy section.

How different I felt looking at these books! They seemed to hold the promise of life and adventure. You might say that comics, having kindled in me the desire to read, are my first love; but, fantasy works were my second. Shortly after reading The First King of Shannara during grammar school, I devoured Terry Brook’s works and soon joined the Science Fiction Book Club in order to enrich my experience of fantasy to a greater extent. I even wished to be an epic fantasy writer á la Tolkien. I confess to have discarded fantasy after college, preferring to concentrate on classic, religious, or historical works as being more useful and esteemed. For a short time, I have felt myself deprived, as anime–whether fantasy or otherwise–did not fill up this whole in my life for the fantastic. Reading Conan the Cimmerian, Latro of the Mist, and The Lord of the Rings gave me a peculiar joy, but I have not been ready to make a full return. Indeed, I returned to my usual fare after these works.

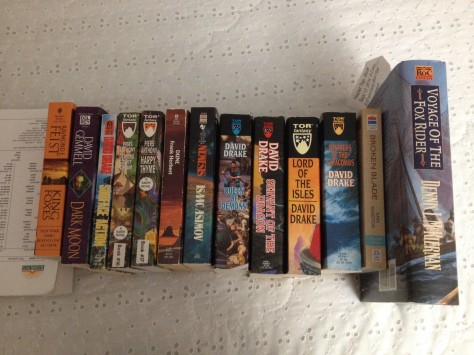

Yet, these fantasy books in the sale! I wonder whether I hid my excitement as I beheld familiar authors like David Drake, Terry Goodkind, Raymond Feist, Piers Anthony, Terry Brooks, and the rest. That which was once my great love stood stretched out before my eye. Initially, I thought that I would pick up a few books. Instead, my famished appetite for the fantastic resulted in this impressive haul:

And all for $3.50! Amusingly, the first thing I did when I got home was to open up Wizard for Hire by Jim Butcher. Historical, classic, and religious works may collect a little dust for now.

Wisdom of the Ancients: Martial Book 8, Epigram 23

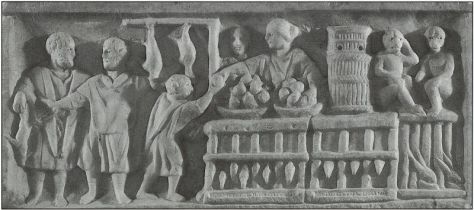

Today, I looked for an epigram which fulfilled the conditions of being short and simple. Though the twenty-third epigram of Martial’s eighth book does not offer as complicated ideas as the last one I examined, it has a great punch line.

Esse tibi videor saevus nimiumque gulosus,

Qui propter cenam, Rustice, caedo cocum.

Si levis ista tibi flagrorum causa videtur,

Ex qua vis causa vapulet ergo cocus?

I seem to you to be savage and too dainty,

Rusticus, I who, on account of dinner, beat my cook.

If this cause seems trivial to you for whipping,

From what cause therefore do you wish that my cook be whipped?

Analysis of Poem

Not much to this poem. I might add that this is the only place where the name Rusticus appears in Martial’s works, and the name implies that Martial’s guest is unsophisticated. He’s a stoic on the level of Cato who does not recognize the importance of fine dining. Therefore, he thinks that a cook does not deserve to be beaten for preparing inferior food, but Martial thinks otherwise.

The way Martial ends lines two and four with cocus seem to emphasize that he is speaking about a cook. Though, caedo cocum mocks the opinion of Rusticus that his beating of the cook is savage. For, caedo cocum could–in another context–mean “I cut down the cook” or “I killed the cook,” which is clearly an excessive punishment for making poor food!

Other than that, this poem features some nice use of alliteration which adds to the light feel of the poem. The second line in particular is stuffed with k sounds. The last features an interlocking order between the v’s and c sounds. (Qua and causa have a similar consonantial quality.) They serve to emphasize Martial’s point at the end: a cook’s only job is to cook. Why else should he be punished except for making bad food?

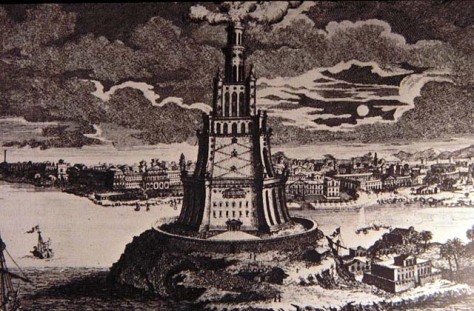

Wisdom of the Ancients: Martial – Book X, Epigram IV

While in my senior year of college, I discovered Ovid’s Erotic Poems. Reading a few of them to my friends convinced them that they were too funny to keep to ourselves. And so, my entire floor of the dormitory was invited to hear the poems. This series of readings won the affectionate nickname “Wisdom of the Ancients” and continued until I ran out of Ovid and turned to Catullus. Unfortunately, these poems proved too disturbing for the members of my hall, and the series ended promptly.

I promise not to post any profane Catullus here–especially since he can write beautifully when he wants. Instead, I’ll start with some of the best of Martial’s epigrams. One of which, I have already posted about. Essentially, I shall use the same format as was used in that article: writing the poem in the original, translating the poem, and elucidating on the ideas contained therein. I hope to be able to do this daily. Today, this series starts with the fourth epigram of Martial’s tenth book of epigrams. Enjoy!

Qui legis Oedipoden caligantemque Thyesten,

Colchidas et Scyllas, quid nisi monstra legis?

Quid tibi raptus Hylas, quid Parthenopaeus et Attis,

Quid tibi dormitor proderit Endymion?

5Exutusve puer pinnis labentibus? aut qui

Odit amatrices Hermaphroditus aquas?

Quid te vana iuvant miserae ludibria chartae?

Hoc lege, quod possit dicere vita ‘Meum est.’

Non hic Centauros, non Gorgonas Harpyiasque

10Invenies: hominem pagina nostra sapit.

Sed non vis, Mamurra, tuos cognoscere mores

Nec te scire: legas Aetia Callimachi.

You who read about Oedipus and endarkening Thyestes,

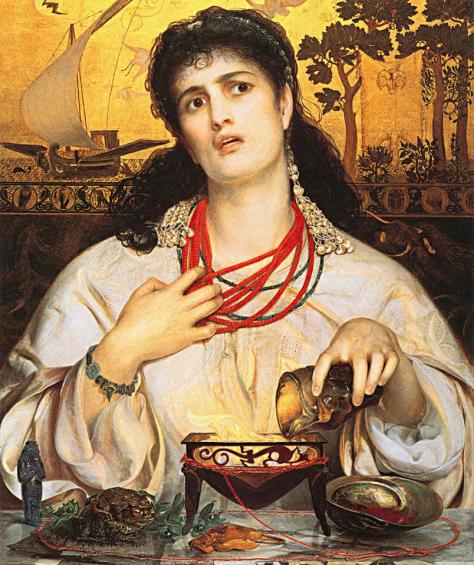

Medeas and Scyllas, what are you reading about except monsters?

What help to you is stolen Hylas? What good to you is Parthenopaeus and Attis?

What benefit is the sleeper Endymion to you?

Or the boy slipped of his falling wings? Or Hermaphroditus

Who hates the watery mistress?

Do these empty laughing-stocks of a miserable page help you?

Read this work of mine, because Life can say “The work belongs to me.”

Here, you will find no Centaurs, Gorgons, and Harpies:

Our pages understand man.

But you wish, Mamurra, neither to recognize your ways

nor to know yourself: may you read Callimachus’s Aetia.

Analysis of the Epigram’s Themes

The proper names are organized in a beautiful way so that the word monstra strikes the reader more strongly. After all, Oedipus and Thyestes are people–as is Colchidas, literally “women of Colchis” refering to its most famous personage, Medea. Scylla is the only being having the form of a monster, but Oedipus for sleeping with his mother, Thyestes for eating his son, and Medea for slaying her sons are all monsters through their deeds. The fact that Oedipus and Thyestes are singular while Medea and Scylla are written in the plural form reflect on the repetitiveness of epic. Even though Oedipus’ and Thyestes’ crimes are singular, many epics are written about them–the same as we see with Medea and Scylla.

Another thing to reflect on in the first two lines lies in that Oedipus and Thyestes unwittingly did wrong. Also, Scylla is a monster and so has neither rational or moral agency. Why is Medea there then when she wittingly slew her two children in order to revenge herself on Jason? It cannot but be because the ancient pagans viewed women as irrational. Just a little example of ancient mysogyny and perhaps even the trepidation with which men held women in the ancient world. Naturally, men are stronger than women, but one always views beings which one considers irrational with a bit of fear. Hence, women were kept locked up by their fathers and husbands in the ancient world lest they follow their passions and disgrace the family through adultery or fornication. Thus, the first two lines strike us with the irrationality and unreality of epic.

The next four lines contain examples of pretty boys. When we think of epic, we usually think of heroes like Hercules, Achilles, Odysseus, etc. But, Martial would have us focus instead on the many pretty boys who have little agency in the stories featuring them and are pushed around by fate. Even the most masculine of them, Parthenopaeus of the Seven against Thebes, becomes diminished by his association with boys who became love slaves of various goddesses and nymphs. His masculinity is especially painted with dark colors by being placed next to Attis, who castrated himself in order to become the devotee of the goddess Cybele. Lastly, Hermaphroditus hates the watery mistress because a certain nymph attempted to rape him while he swam in her waters–the ultimate form of emasculation. Even the position of Hermaphroditus between amatrices and aquas give the impression of him being overwhelmed. But, he must submit to fate no matter how much he hates it. All this asks how epic can produce good men when we see so many examples of boys on one hand and monsters on the other.

The Latin word ludibria in line seven can mean mockery, derision, object of derision, laughingstock, or plaything. It seems to refer to all the “heroes” of the epics above as well as to the epics themselves, which are vana–“empty or vain.” I also believe that the position of vana colors iuvant to indicate that epics are vain helps to understanding life. Also, one might be tempted to look at miserae chartae (“of a miserable page”) as miserarum chartarum (“of miserable pages”). But, the latter, by being plural, seems to condemn only certain works of epic and myth, while the singular condemns the whole class of mythology and epic to perdition, making miserae chartae much stronger. All epic is cut from the same silly cloth!

In the next line, Martial personifies life–vita–as if to show Life itself giving an endorsement of his poetry. It is also worth noting that this line and the next three provide and interlocking order of themes: real life, myth, real life, myth. The last line contains the philosophical dictum te scire–“to know thyself”–in opposition to Callimachus’s Aetia, which may correctly be called a work of belles lettres. The epigram asks the reader to choose between real knowledge and fantasy. (St. Augustine, if he read this poem, must have loved it.)

To end this article, I must say that I love the juxtaposition of Mamurra and Callimachus in the final lines. Mamurra was one of Julius Caesar’s henchmen, while Callimachus was a famous Alexandrian poet. Martial offers the chance to Mamurra to learn to repent of his evil life through reading works which show how to live a good life–poetry based on reality and philosophy. On the other hand, Callimachus seems to be even more criminal than Mamurra by having written such nonsense as Aetia. The poem even suggests that myth produces such criminals as Mamurra.